CBS doctoral scholar explores the management of sickle cell disease in India

By Sanghamitra Das, a 5th-year Biology and Society graduate student pursuing the Bioethics, Policy and Law track with Dr. Lindsay Smith.

What can the world gain from an anthropological investigation of sickle cell disease in India? This question has been at the heart of my recent fieldwork with sickle cell communities in India. Globally, sickle cell disease—a rare genetic blood disorder—has been racialized as a “Black” disease, yet it affects communities in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia. In the caste-based society of India, though this genetic condition is found across communities, sickle cell disease has been biomedically mapped onto indigenous and marginalized communities that are historically and socioeconomically oppressed.

My doctoral dissertation investigates how such an association of sickle cell disease with indigenous and marginalized communities influences public health policies and the political economy of sickle cell care in India. At the same time, my dissertation also interrogates how the association of sickle cell disease with these communities, despite its incidence among socioeconomically advantaged social groups, is unsettled by the lived experiences of sickle communities in India.

Sickle cell disease is a result of a point mutation in the gene coding for the hemoglobin molecule. This mutation causes red blood cells to become sickle-shaped, sticky, and short-lived, leading to the obstruction of blood flow that causes intense episodes of pain known as “pain crises.” My quest to understand the lived experiences and management of sickle cell disease within varying health systems in India, primarily in resource-constrained settings, took me to three field sites in three different regions in India. This multi-sited approach allowed me to witness the tensions between top-down governance and local particularities. In other words, I interrogated how the governance of sickle cell management in the form of public health policies focusing on emerging therapies is unsettled by the local particularities of access to basic medical care in the resource-constrained public health system of India.

I carried out my research in collaboration with sickle cell patients and their families, community members, patient advocates, physicians, scientists, and community health workers. The findings from my fieldwork support the argument drawn from medical anthropology that how we experience disease and well-being transcends our bodily condition to include the sociopolitical and economic circumstances that shape our experience of affliction. In other words, experiences of health and sickness are shaped by the larger everyday circumstances of our societies. Drawing upon theoretical tenets in the social studies of science, my research illuminates how assumptions about biological difference are embedded in the knowledge production around sickle cell disease in India. In particular, utilizing documentary analysis, I traced the epistemic processes through which sickle cell disease came to be characterized as a disease of the indigenous and the marginalized in the biomedical history of India. Such notions of genetic difference, which in turn are derived from the logic of the caste-based social hierarchy in India, consequently get restabilized as alleged social facts. How do communities that are already marginalized interact and engage with such so-called social facts, particularly in light of emerging pharmaceutical research for novel drugs and genetic therapies targeting sickle cell disease both nationally and globally? This has been a central question guiding my dissertation research.

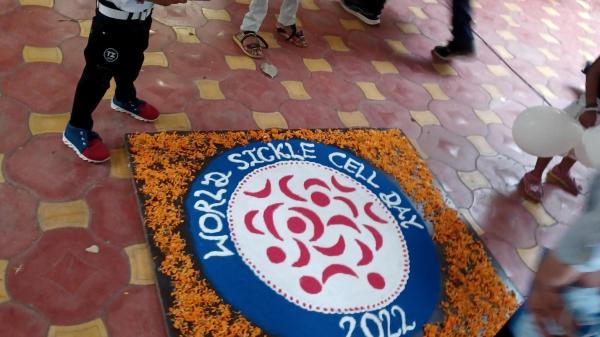

The fieldwork for this dissertation project was carried out for 14 months between July 2021 and August 2022, and was made possible by the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant; the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship; and the Top-Up Fellowship from the School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University. Moreover, this research would have been impossible without the support of local organizations and the sickle cell communities with whom I have formed a lasting relationship.

I conceptualized this study and actualized it at a time when the world was battling a global pandemic. Disarmed of the established anthropological methods of immersion in communities through ethnographic research, I adapted my research to respond to the contingencies of the pandemic. As a result, I have now developed valuable expertise in digital ethnographic methods that are both ethical and decolonial, attentive to the situated realities of the communities that we as researchers work with. These methods include utilizing encrypted online platforms like Zoom and WhatsApp for carrying out online interviews as well as conducting remote participant observation in online scientific webinars, patient advocacy meetings, and community events. Although my research entailed in-person research eventually, the pandemic taught me a valuable lesson in human creativity and interpersonal connection that have the capacity to span both uncertainty and adversity.