Bringing Microbiology to Life: A Bio & Society Alum’s Approach to Teaching

By: Matt Tontonoz

BIO205 at Chandler-Gilbert Community College is not your typical microbiology class—at least not when Karen Wellner teaches it. Dr. Wellner has two doctorates, one in Science Education from the University of Iowa and one in Biology and Society from ASU. As if that weren’t enough, she also has a master’s degree in urban planning from Iowa and a master’s degree’s worth of credits in microbiology from San Diego State University, as well as training as a clinical microbiologist. All that education and expertise means that Dr. Wellner can speak just as authoritatively about the pathology of disease as about its history and social determinants.

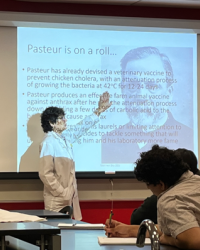

On the day that I am visiting her class, Wellner is teaching students about the rabies virus, which she describes as “a most diabolical virus.” Its case-to-fatality ratio, she notes, is 100 percent.

Wellner weaves seamlessly between discussions of the structure of the virus, routes of transmission and infection, and Louis Pasteur’s classic work developing a rabies vaccine. She moves swiftly between the white board, where she sketches out Pasteur’s experimental approach, and PowerPoint images showing EM images of the bullet-shaped virus.

Most of the students in Dr. Wellner’s class are pre-nursing. Some will go on to be physician assistants. A few will pursue graduate work in biology or related disciplines. For many, they are the first ones in their family to go to college. Graduates of Chandler-Gilbert will earn an associate’s degree. Nearly all of them will continue on to earn a bachelor’s.

Dr. Wellner’s goals for the class are more than simply teaching students about the details of microbiology.

“My big thing is to make them see the world in a different way than they did before,” Dr. Wellner says. “That’s what I think education is about.”

Learning through Doing

The part of the course that likely has the biggest impact on students is something called the Polio Project, which Dr. Wellner created nearly 20 years ago. The project involves having students conduct interviews with older family members and friends who either had a polio infection or knew someone who did. The goal is for them to use what they learn from their interviews to reconstruct the symptoms, routes of transmissions, and physical consequences of poliovirus infection.

“They’re constructing their own knowledge,” Dr. Wellner explains. She knows the value of this pedagogical approach in part through her graduate work in science education; she wrote her doctoral dissertation on the spatial development ideas of psychologist Jean Piaget and their relevance to the classroom.

The other thing the project teaches them, Dr. Wellner notes, is what she calls intellectual empathy. “Most of them are going into healthcare because they want to help people, but they don’t really learn very much about that in their basic science classes. It’s all bugs and mitosis. Hearing stories from people affected by polio, and how people were treated—it lets some of that empathy come out,” she says.

A Passion for the History of Science

At ASU, Dr. Wellner wrote her dissertation on Ernst Haeckel’s embryological drawings. Her advisor was Jane Maienschein, the director of the Center for Biology and Society, with whom she co-taught the Embryo Project writing seminar for a time.

Dr. Wellner’s current classroom reflects the time she spent at ASU pursuing the history of science. It’s covered in posters advertising academic symposia and events from that time, as well as historical public health posters about various contagious diseases.

Having taught consistently for the past 40 years, Dr. Wellner is considering hanging up her teaching cap in the next couple of semesters. But she won’t be leaving the world of science and ideas. She’ll be conducting original research in the history of science, including for a book that examines material culture in biology education, 1900–1980. She also has an article coming out soon about two University of Iowa botanists, Thomas Macbride and Bohumil Shimek, who contributed to the creation of a national scientific community and the rise of American science in the late 1800s.

“It’s mostly for fun,” she says. You know what Jane [Maienschein] says: ‘Don’t do it unless it’s fun.’ That’s how I think about my work in the history of science.”